Trauma in Child-Serving Settings

In the decades since the CDC-Kaiser Permanente study of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), researchers have learned more about the troubling effects of trauma on children and adolescents. Unfortunately, insights from new discoveries do not always find their way to schools, health care settings, and community centers—the child-serving organizations best equipped to provide support. As a result, many children experience the effects of trauma without the supports and services they need to cope. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these issues.

Trauma ScreenTIME and Educate-SMART (School Mental Health Awareness and Response Training) will make it easier for child-serving professionals to identify and address trauma in young people. The Child Health and Development Institute (CHDI) worked with 3C Institute to develop these trainings, both of which tackle rising rates of trauma exposure and behavioral health disorders through 3C’s innovative DeLP (Dynamic e-Learning Platform) technology.

Many children face the effects of trauma without the supports and services they need to cope.

Trauma ScreenTIME

Developed by a team of national experts led by Dr. Jason Lang, vice president for mental health initiatives at CHDI, Trauma ScreenTIME focuses on a step often overlooked in discussions of treatment: screening. By outlining the process and considerations involved in screening, the training gives professionals the tools they need to recognize signs that children may have been exposed to trauma. Trauma screening can connect children and their families with relevant supports and services, and it can also encourage discussions about trauma.

All too often, inadequate screening acts as a barrier to the resources, supports, and treatments needed to cope with trauma exposure. Dr. Larke Nahme Huang explains that “asking children and caregivers about trauma can be intimidating, even for experienced staff.” Trauma ScreenTIME is designed to overcome these obstacles. “The ScreenTIME course,” Larke continues, “details everything you need to know, from how to screen a child to developing an effective screening process tailored to your organization.”

Trauma ScreenTIME guides professionals through this complex process through its core course consisting of five self-paced modules. Each module centers on an important question:

- Why screen for trauma and traumatic stress?

- How do you develop a screening process for your program or organization?

- How do you select a screening measure?

- How do you screen a child for trauma?

- How do you use the results from trauma screening?

Additional courses, each focused on a particular child-serving setting, including schools, the juvenile justice and child welfare systems, and pediatric primary care, will become available over the next several years.

Educate-SMART

Like Trauma ScreenTIME, Educate-SMART seeks to help students exposed to trauma. But it takes a broader view of the problem, exploring several domains where trauma can occur and how it can be addressed. Spanning 18 lessons across nine modules, Educate-SMART provides comprehensive trauma-informed behavioral health guidance for such issues as:

- Mobile crisis intervention services

- Suicidality

- Trauma’s effects on learning and behavior

- Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma

- Transferring feelings between students and school staff members

- School climate and equity

- Behavioral supports and systems

- Childhood development

These and other topics make Educate-SMART a one-stop training portal for school staff members, caregivers, and even students. Dr. Jamie LoCurto, senior associate at CHDI and lead developer for Educate-SMART, notes, “districts have increasingly recognized the importance of integrating comprehensive trauma-informed behavioral health programming into their strategic plans. Educate-SMART was created to train school staff, community providers, and students and their families in the relevant behavioral health topics needed to implement comprehensive behavioral health in schools.”

Unlike many programs, however, Educate-SMART offers a fully customizable training experience. Learners’ roles determine their set of required lessons, and each participating district can configure these requirements differently. In practice, this level of customization means that learners take lessons most pertinent to their responsibilities and school environment.

Districts have increasingly recognized the importance of integrating comprehensive trauma-informed behavioral health programming into their strategic plans. Educate-SMART was created to train school staff, community providers, and students and their families in the relevant behavioral health topics needed to implement comprehensive behavioral health in schools.

Jamie Locurto, PhD, Senior Associate at CHDI and Lead Developer for Educate-SMART

The training portal is currently available to staff in Middletown Public Schools, Naugatuck Public Schools, and Windham Public Schools. CHDI plans to make Educate-SMART available to other districts in Connecticut later on.

E-Learning and the Power of DeLP

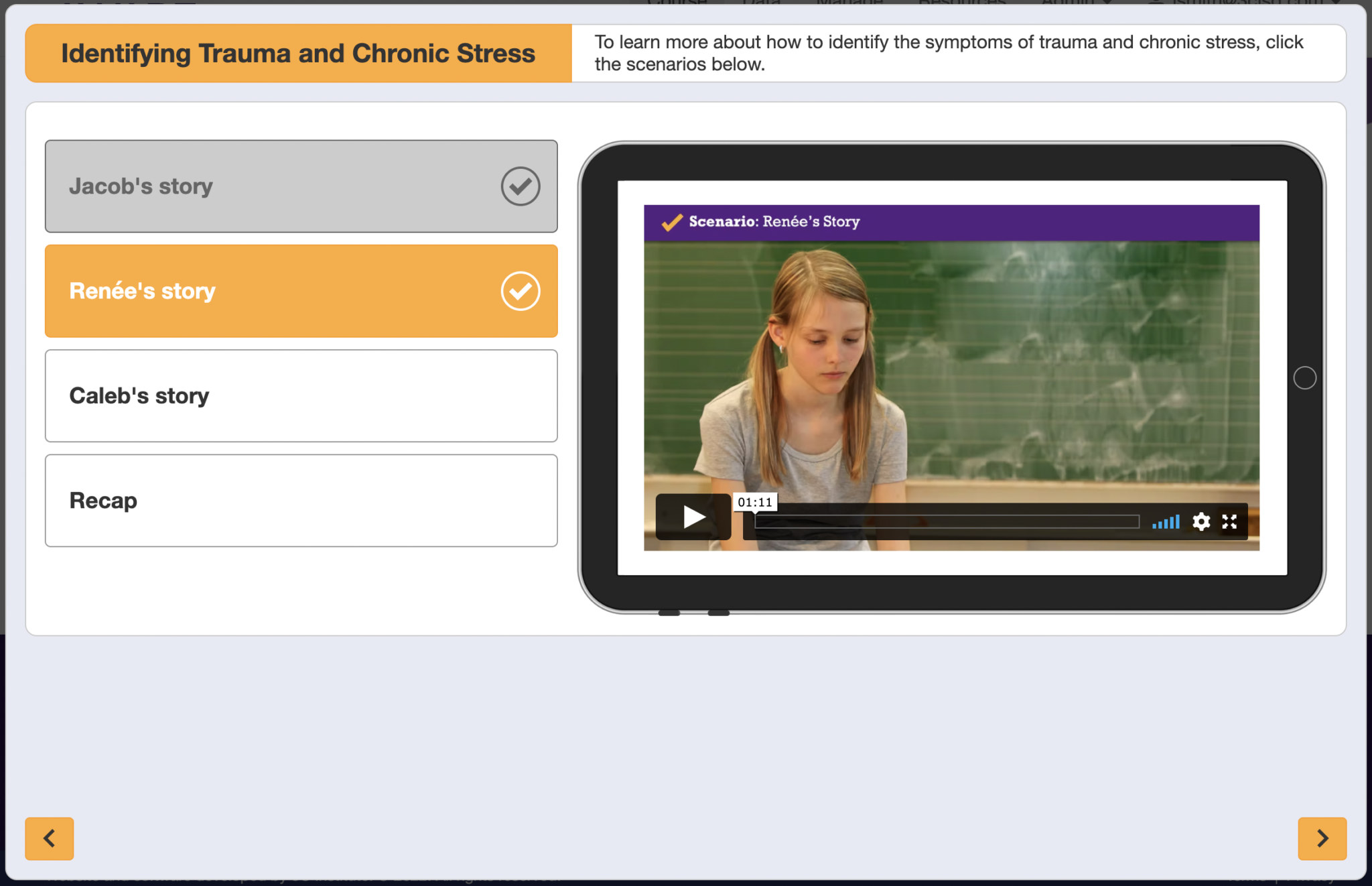

To take learners through such varied and complex content, Trauma ScreenTIME and Educate-SMART both rely on best practices for e-learning. As learners go through 3C’s proven Tell Me, Show Me, Let Me Try method, they:

- Build their knowledge through informational videos that mix onscreen actors and animations

- Test their understanding through knowledge checks, self-reflections, and drag-and-drop activities

- Apply concepts through scenarios and scenario-based questions

Trauma-Informed Programs for a Trauma-Affected World

As the ACEs study shows, trauma takes many forms, and its effects are often long-lasting. For young people, the effects can be especially detrimental, as they do not yet have the social, cognitive, or behavioral skills needed to cope with traumatic experiences. Trainings such as Trauma ScreenTIME and Educate-SMART represent much-needed efforts not only to promote these skills but also to foster greater trauma awareness at home, in schools, and in communities. These are efforts worth making.